This is part six of a series of articles that take a closer look on the relationship between increasing human population levels and the food production system that sustains human livelihoods. While part five examined conventional agriculture, this post will look on the possibilities and realities of organic farming to feed a growing population.

Organic farming is an agriculture system that has a more holistic approach in which it uses methods that are designed to be less damaging to ecosystem services and the natural resource base. Organic farming does this by emphasizing the overall health of the agro-ecosystem by promoting and enhancing local biodiversity and biological activity in the soil, recycling its own waste from crops and livestock so that it can return valuable nutrients to the land, improving and maintaining soil-fertility, minimizing all forms of agriculture-related pollution and its impact on the environment, among other things. Instead of synthetic materials and off-farm inputs organic farmers are keener on using on-farm resources and management practices which involve cultural, biological and mechanical methods. This does not mean that organic farming is hostile towards technology. Organic farmers have no problems with utilizing modern technology selectively while avoiding those practices or technological elements which are risky and possibly harmful for the environment. While conventional agriculture is free to use various practices, organic farming is subject to both national and international regulations which limit them in their options and practices. These certification standards and regulations may differ depending on country and region, but they all restrict the use of pesticides, fertilizers and certain forms of genetically modified crops organisms.

As the demand for healthy food and environmental concerns are becoming more important for consumers around the world, alternative approaches to agriculture have become less alternative and more mainstream. Organic farming enterprises are emerging from the now profitable business and its products are no longer restricted to niche health food stores or farmers' markets. Despite this recent progress for alternative agriculture practices, the skepticism against organic farming is still strong. Ehrlich predicted that the use of pesticide and conventional practices would intensify, and that the ecological aspect of agriculture would be "ignored more and more" as population numbers increased and produce became scarcer. Critics argue that organic agriculture isn't more environmentally friendly as it requires more land to be converted to farmland to be able to reach similar yields levels as conventional farming. Critics also argue that vegetables that have been organically grown in greenhouses around Europe are much less sustainable than their conventional counterparts from Africa. Many people are also skeptical to claims that organic food is healthier or that it would contain more nutrients. Most of the criticism against organic farming revolves around the smaller yields the alternative system produces compared to the more conventional methods.

The Possibilities of Organic Farming

The UNEP report mentioned in part five forecasts that food will rise in demand as human population grows by about two billion more individuals, incomes increases and the growing consumption for meat continues unhindered. The report warns that although global food production "rose substantially in the past century", mainly thanks to agricultural expansion as well as fertilizers and irrigation, yields have in the last decade nearly stabilized for cereals. According to their estimates it's "uncertain" that further yield increases can be achieved. If they are possible to achieve, they will most likely be too small and thus unable to keep pace with the growing food demand. UNEP blames the leveling of yield increases partly on a lack of investments in agricultural research and development. But more so they warn about the negative effects on future crop yield levels that urban expansions, soil and environmental degradation, increased biofuel production, and anthropogenic climate change will have. The combined effects of all these has the potential to reduce projected yields by 5-25 percent by 2050. This would cause food shortages, with food production being up to 25 percent short of demand, and prices that are 30-50 percent higher than today. This scenario could be averted if we manage, while increasing yields, to optimize our food chain system. This is possible to accomplish by minimizing the loss of food energy from each step of the food production chain - from harvest and process to consumption and recycling. But more importantly, we need a "major shift" towards "more eco-based production" (read: organic farming) that can help reverse soil degradation, conserve biodiversity and protect ecosystem services.

One study, which examines the relative yield performance between conventional and organic agriculture systems from 66 previous yield studies, shows that organic yields are on average 25 percent smaller than conventional ones. The results in the analysis ranged from 5 percent to 34 percent smaller yields, depending on contextual conditions, for organic farming. This would indicate that organic agriculture requires additional land to be converted into farmland for it to reach similar yield levels as conventional agriculture.

A 13 year side-by-side comparison of organic and conventional corn-soybean systems, at the Iowa State University in the US, shows that organic farms can provide similar yields as conventional agriculture, while at the same time resulting in higher economic returns for the organic farmer. Another similar study is the 30 year side-by-side trial of organic and conventional corn and soybean yields by the Rodale Institute. The Farming Systems Trial (FST) started in 1981 to study the transition from conventional to organic farming procedures as well as compare yield levels between the two agriculture methods. During the first few years of the transition there was a decline in yields for the organic crops. Later on the organic yield levels saw a rebound and today the yield levels match, or in some cases even surpasses the conventional crop yields. Especially interesting are the findings that organic yields will outperform conventional crop yields during years of drought. Studies done on data from the FST confirm this to be the case. A review of the FST by David Pimentel and others from the Cornell University shows that organic agriculture produces the same corn and soybean yields as more conventional farms. During the drought years of 1988-1998, the organic crop yields were 22 percent higher than conventional yields in the trial. Organic farmers in the US say that they have fared better against the recent drought this past summer which severely damaged crops, reduced crop yields and drove up food prices.

A 21 year study of organic and conventional farming systems in Switzerland may show what kind of performance we could expect to see from organic agriculture in Central Europe. The result from the study indicates that organic farming systems in Europe would see cereal crop yields that are on an average 20 percent lower than their conventional counterparts. But at the same time the nutrient input for the organic systems were 34-51 percent lower than in the conventional systems. That results in crops that require 20-56 percent less energy during their life-span, or 36-53 percent lower energy intakes per acre of farmland for organic crops. Therefore, the authors of the study still consider organic agriculture to be an "efficient production" method. The study could only find minor quality differences between the food systems. The organically managed soils showed a greater biological activity and a better floral and faunal diversity than the conventional managed soils. Their conclusion is that organic farming is "a realistic alternative" to conventional agriculture. Profits for the organic farm remained similar to its conventional equivalent. This would indicate that organic farmers could see financial gains from converting to organic agriculture as they need to spend less money on expensive off-farm inputs.

Another study, which compiled data on the current global food supply as well as comparative yields between organic and conventional farming methods, also suggest that its possible for organic agriculture to feed both current and future human populations. The purpose of the study was to try and estimate how much food could be produced after a hypothetical global shift to organic farming. From a plethora of various other studies comparing crop yields between organic and conventional farms, the authors of the study calculated a dataset of 293 examples of global yield ratios for all the major crops in both the developed and developing world. The results showed that organic farming would give smaller yields in the developed world while the organic yields in the developing world would be larger than their current conventional yields. Two different models were then constructed.

The first model applied the yield ratio for developed countries to the entire world, the model assumed that regardless of location all farms would only get the lower developed-country yield levels. For the second model the authors applied the lower organic yield ratios from the developed world to developed countries, the higher organic yield ratios which were measured earlier for the developing world was then applied to those respective countries. The results from the first conservative model indicated that organic farming would generate 2641 kilocalories per person/day. This is a good result, especially considering that the current food supply provides 2786 kilocalories per person/day and that the average caloric requirement for adults is between 2200-2500 kilocalories. The result from the second model was even more promising. It showed that organic farming on a global scale could generate 4381 kilocalories per person/day. This would result in a 75 percent increase in food availability for the world's current population. The results from model two would also result in a food production that could sustain a much larger human population. This increase in food quantity would be possible to achieve while maintaining the current agricultural land base. Organic farming methods could even have the potential to reduce total agricultural land base. If properly intensified, organic agriculture "could produce much of the world's food" and improve food security in developing countries.

But for this transition, from conventional to alternative, to be possible we need to overcome numerous agronomically and economically challenges. The authors of the study calls for increased investments in agricultural R&D. Considering that for the past 50 years most agricultural research has been focused on conventional methods there is huge potential for comparable improvements in yield increasing procedures and pest management methods for organic farming. This is especially the case in developing countries which only spend US$0.55 for every US$100 of agricultural output on public agricultural research and development. This can be compared to US$2.16 for developed countries.

Small farms are being highlighted in many of these studies as an important way to reach global food security. Both in developed and developing countries the production per unit area is greater on smaller farms. Therefore an increase in small farms would have positive effects for global food availability. In fact, and despite the large modern industrial-like farms of today, around 70 percent of the world's food comes from small farms. The widely held belief that the large monocultural farms are the most efficient and productive is a myth; it's actually the smaller farms, many of whom are located in developing countries that are the most efficient in their production. Small farmers manage to maximize the use of their land by using integrated farming systems which involve using a wide variety of crops as well as livestock on the farm. This combination helps provide a range of food and animal products to the local economy as well as supplying the farmer with manure for improving soil fertility. Larger farms might have higher yields per acre of a single crop, but overall the total production per acre of all crops and animal products combined is much higher on smaller farms. This way small farms helps to strengthen the local economy and environment while also improving food security worldwide.

The Realities of Organic Agriculture Today

Despite these promising possibilities for organic farming the reality is that organic farming still plays a very insignificant role in our global food production system.

Total global arable land, which include both crop cultivation and pastures for livestock, is around 13 805 000 km². Of this only 0.9 percent, or around 370 000 km², are organic. In 2010 only seven countries had more than a total of ten percent organic agricultural land. In the beginning of the 21st century, some 17 million hectares of land (nearly 170 000 km²) were dedicated to organic farming globally. In North America around 1.3 million hectares of farmland were farmed organically. The majority, around 45 percent, were located in Oceania, mainly Australia. Europe had 25 percent and Latin America shortly followed with 22 percent. The highest share could be found in the EU with more than three percent of total agricultural land area dedicated to organic farming.

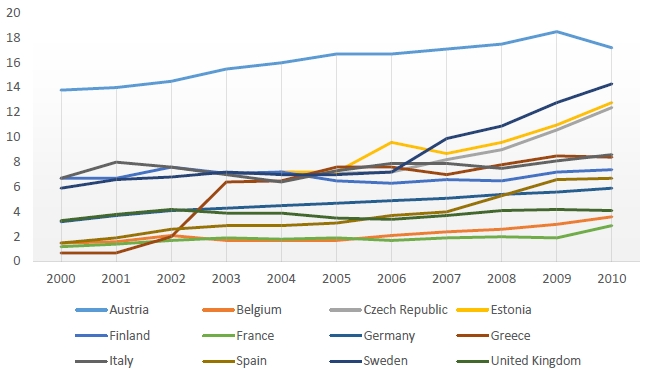

12 EU member states and the share of total organic crop area out of total utilized agricultural area (%) in their respective nations. Data from the Czech Republic and Estonia are not available until after 2002 and 2003 respectively. Source: EUROSTAT.

When it comes to organic farming policy, the "EU leads the world." Various policies and political mandates in support of organic development have been in place in the EU since late 1980. In 1991, ten years before the equivalent US legislation came; the EU introduced consistent labeling of agricultural products and food across all member states. In the past two decades the amount of EU land dedicated to organic agriculture has seen a dramatic increase. Organic farmland increased five-fold just during 1993-2000. This development is expected to continue thanks to continued growth in consumer demand for organic products and various government incentives and mandates. Total organic land area, i.e. fully converted land area as well as land area under conversion from conventional to organic farmland, in EU27 increased from 3.6 to 4.1 percent 2005-2007. In 2008, organic farmland covered a total of 7.8 million hectares. The total organic area continues to show an upward growth trend in the union. During 2006-2007 the increase was 5.9 percent. 2007-2008 organic farmland increased with 7.4 percent. The five member states with the largest organic area for EU27 is Spain (1.3 m/ha), Italy (1.0 m/ha), Germany (0.9 m/ha), UK (0.7 m/ha) and France (0.6 m/ha). Figure 6 shows how the size of organic farmland varies greatly from one member state to another with some states making more progress than others. The graph shows how Sweden's farmland has increased from 5.9 percent to 14.3 percent during 2000-2010. Other countries haven't seen a similar development during this period. The UK increased their share with less than one percent, going from 3.3 to only 4.1 percent.

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.