Politicians, lobbyists, and tourists alike can ride bicycles along a specially marked lane between the White House and the U.S. Capitol, part of the 115 miles of bicycle lanes and paths that now crisscross Washington, DC. In Copenhagen, commuters can ride to work following a “green wave†of signal lights timed for bikers. Residents in China’s “happiest city,†Hangzhou, can move easily from public transit onto physically separated bike tracks that have been carved out of the vast majority of roadways. And on any given Sunday in Mexico City, some 15,000 cyclists join together on a circuit of major thoroughfares closed to motorized traffic. What is even more exciting is that in each of these locations, people can jump right into cycling without even owning a bicycle. Welcome to the era of the Bike Share.

Cyclists have long entreated drivers to “share the road.†Now what is being shared is not only the road but the bicycle itself. Forward-thinking cities are turning back to the humble bicycle as a way to enhance mobility, alleviate automotive congestion, reduce air pollution, boost health, support local businesses, and attract more young people. Bike-sharing systems—distributed networks of public bicycles used for short trips—that integrate into robust transit networks are being embraced by a growing number of people in the urbanizing world who are starting to view car ownership as more of a hassle than a rite of passage.

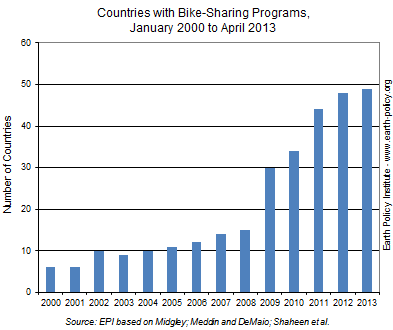

Today more than 500 cities in 49 countries host advanced bike-sharing programs, with a combined fleet of over 500,000 bicycles. Urban transport advisor Peter Midgley notes that “bike sharing has experienced the fastest growth of any mode of transport in the history of the planet.†It certainly has come a long way since 1965, when 50 bicycles were painted white and scattered around Amsterdam for anyone to pick up and use free of charge. Unfortunately, many of those bikes quickly disappeared or were damaged. In the 1990s, several Danish cities began more formal systems, with designated racks and coin deposits to check out bicycles. Copenhagen’s famed Bycyklen (“City Bikeâ€) program, which has been an inspiration to many cities, finally closed at the end of 2012 after operating for 17 years with more than 1,000 bicycles. It is set to be replaced by a modern system in 2013, which could help Copenhagen meet its goal of increasing the share of commuting trips on bike from an already impressive 36 percent to 50 percent.

Modern bike-sharing systems have greatly reduced the theft and vandalism that hindered earlier programs by using easily identified specialty bicycles with unique parts that would have little value to a thief, by monitoring the cycles’ locations with radio frequency or GPS, and by requiring credit card payment or smart-card-based membership in order to check out bikes. In most systems, after paying a daily, weekly, monthly, or annual membership fee, riders can pick up a bicycle locked to a well-marked bike rack or electronic docking station for a short ride (typically an hour or less) at no additional cost and return it to any station within the system. Riding longer than the program’s specified amount of time generally incurs additional fees to maximize the number of bikes available.

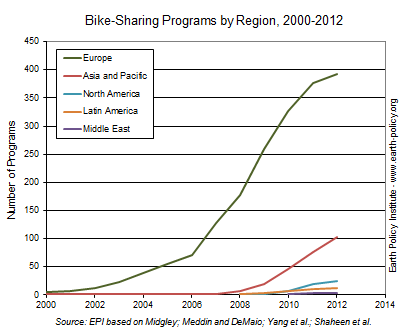

Although the Netherlands and Denmark had far more pervasive cycling cultures, it was France that ushered the world into the third generation of bike sharing in 1998, when advertising company Clear Channel began the world’s first public computerized program with 200 bikes in the city of Rennes. The country moved into the big leagues in 2005 when Lyon, France’s third largest city, opened its Vélo’v program with 1,500 bikes at some 100 automated self-service docking stations. Its success—an apparent 44 percent increase in bicycle ridership in the first year—paved the way for large-scale bike sharing’s early shining star: the Vélib’ in Paris.

Vélib’ was launched in 2007 with 10,000 bicycles at 750 stations, and it quickly doubled in size. By the end of 2012, Vélib’, which is funded in a 10-year contract with advertising firm JCDecaux in exchange for street-side ad space, could claim more than 224,000 annual members and had surpassed 130 million trips. Since the system’s launch, the number of cyclists on the streets has risen 41 percent, with more than one out of every three bicycles on Paris streets being a shared bike. With bikes accounting for just 3 percent of traffic, though, there is still room for growth, and that is the plan. Bike sharing is part of a broader initiative to reduce automotive traffic and pollution in Paris, which includes closing prominent streets to cars on weekends, reducing speed limits, marking dedicated bus lanes to help move people en masse more efficiently, and extending the bike lanes network to 430 miles (700 kilometers) by 2014—all championed by Paris Mayor Bertrand Delanoë, who has said that “automobiles no longer have a place in the big cities of our times.â€

Meanwhile, programs were popping up throughout Italy and Spain like mushrooms after a rainfall. According to figures maintained by Peter Midgley, Italy had 47 bike-sharing programs in 2007, Spain had 36, and France had 18. Many were smaller scale, with tens of bikes rather than thousands. But a few stand out. Spain’s signature program in Barcelona became so popular soon after its launch in 2007—getting many new riders to try bike commuting for the first time—that by 2008 it had quadrupled its fleet to 6,000 bikes and planned extensions to the surrounding communities. Seville also began bike sharing in 2007 as part of a rapid transformation to make the central city more accommodating to people, not just cars. In less than 5 years, cycling leapt from close to nothing to cover 6 percent of trips. As of late 2012, Spain leads the world with 132 separate bike-share programs. Italy has 104, and France, 37. With a wave of new openings in 2009 and 2010, Germany joined the group of leading countries and now has 43 programs, including some with stationless bikes that can be located and accessed by mobile phone. (See data.)

Other European countries have fewer programs, but some are very active. Dublin’s 550-bike system boasts a high membership and frequent rides on each bike. London’s Barclays Cycle Hire system launched in 2010 with 6,000 bikes and has grown beyond 8,000. As part of Mayor Boris Johnson’s “cycling revolution,†London is introducing several new cycle paths and “superhighways†in hopes of doubling the number of cycling trips within the next decade. In the Netherlands, a different breed of bike sharing run by the national railroad makes some 5,000 bikes available at more than 240 rail stations and other popular commuting spots. In Eastern Europe, which appears to be on the brink of a bike-sharing bonanza, Warsaw opened a program in August 2012 with 1,000 bikes that were ridden 130,000 times in that first month. The city now has some 2,500 shared bikes.

Bike-sharing enthusiasm has spread to Eastern Asia, Australia, and the Americas as well. Russell Meddin, who along with Paul DeMaio has chronicled and mapped the world’s bike-sharing programs, reports that even Dubai launched a program in February 2013.

In the Americas, where the car has long been king, the first big third-generation bike-sharing program opened in Montreal in 2009. It now has 5,120 bicycles and over 400 stations, facilitating use of the city’s robust network of bike lanes and paths. Toronto plans to expand its 1,000-bike scheme, and Vancouver and Calgary, along with several other Canadian cities, are expecting to start programs in the next couple of years.

When Mexico City launched its Ecobici program with some 1,000 bikes in 2010, it quickly reached its limit of 30,000 annual members and started a waiting list of eager would-be cyclists. The program has since quadrupled in size and remains the largest of Latin America’s dozen or so programs. Most of these are in Brazil; in fact, São Paulo even hosts multiple bike-sharing ventures. In Argentina, Buenos Aires opened a pilot program in 2010 and currently has 1,200 shared-bikes, allowing more two-wheelers to brave the traffic, even crossing what is known as the world’s widest street. Santiago, Chile, currently has a program operating with 180 bikes at 18 manned stations in one city neighborhood, but later this year plans to roll out a larger automated system that could grow to 3,000 bikes at 300 stations within four years.

Throughout the United States bike-sharing programs are springing up at a fast clip; in fact it is hard to find a sizable U.S. city that is not at least exploring the bike-sharing option. As of April 2013, there were 26 active modern public programs in the United States, a number poised to double within the next year or two.

The largest U.S. program in early 2013 was Capital Bikeshare, with more than 1,800 bicycles spread across 200 stations in Washington, DC, and neighboring communities. Nice Ride Minnesota, which covers the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, was second, with 1,550 bikes at 170 stations. The Boston metropolitan area is home to 1,100 shared bikes. Miami Beach is planning to add 500 bikes to its current fleet of 1,000 as it extends into Miami this year. And Denver, which is looking to grow from near 500 to 700 bikes in 2013, is one of more than 15 public systems in the B-cycle family that give members access to bikes when they travel to different cities, including Madison, Fort Worth, Fort Lauderdale, San Antonio, Charlotte, and Kansas City.

Several of the new players coming online in 2013 will dwarf the existing American field. New York’s highly anticipated Citi Bike program is poised to roll out 5,500 bicycles at 293 stations in Manhattan and Brooklyn in May, with the ultimate goal of reaching 10,000 bikes. Chicago plans to start in June, ramping up to 4,000 bikes at 400 stations in 2014. Southern California will be rolling into bike sharing in a big way with programs opening in Los Angeles (4,000 cycles), Long Beach (2,500), and San Diego (1,800). In northern California, a pilot project of up to 1,000 bikes in San Francisco and Bay Area cities south along the rail line hopes to begin what could ultimately be a 10,000-bike program.

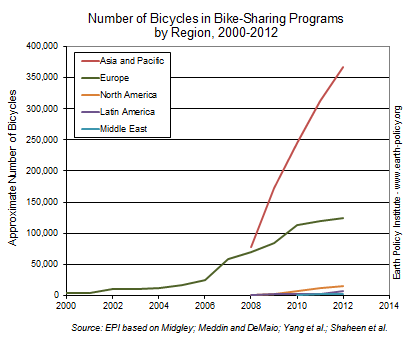

Impressive as these additions are, they are hard-pressed to hold a candle to some of Asia’s massive developments. According to Susan Shaheen and colleagues at the University of California at Berkeley, Asia got into the game in 1999 with a program in Singapore that lasted until 2007. The city now has two bike-sharing systems: one conventional and one run by a car-sharing company offering electric bikes. South Korea rolled out six programs between 2008 and 2010, including one in Changwon that now has 4,600 bikes and one in Goyang with 3,000. Japan, where commuters have a long history of using bikes to get to train stations (witness the 2.1 million bicycle parking spaces in the Greater Tokyo metropolitan area), has nine bike-sharing programs that began between 2009 and 2012. Taiwan, a high grossing bicycle exporter, has two bike-sharing programs as well. But it is the “bicycle kingdom†of China that is showing the world how big bike sharing can get.

In early 2013, China was home to 79 bike-sharing programs, with a whopping combined fleet of some 358,000 bicycles. According to a paper prepared in late 2012 for the Transportation Research Board’s 92nd Annual Meeting by Yang Tang and colleagues at Tongji University, expansions and new projects could soon balloon China’s public bike fleet to just under 1 million cycles.

The world’s largest bike-sharing program is in Wuhan, China’s sixth largest city, with 9 million people and 90,000 shared bikes. Wuhan recently claimed the number one spot from Hangzhou, which has 69,750 bikes in its bike-share scheme. Hangzhou launched mainland China’s first computerized bike-share system in 2008, integrating stations with bus and subway networks, allowing the same transit card to be used across all modes and granting extra free bike riding time with a bus transfer. By 2020 Hangzhou’s system could grow to 175,000 bikes.

The growth in bike sharing and bike infrastructure may help buck the pervasive motorization that has turned rush-hour roadways in China’s fast-growing cities into virtual parking lots. In Zhuzhou, after a program of 20,000 bikes opened in 2011, the share of trips made by bicycle—which had slipped to a meager (by Chinese standards) 5 percent—reportedly jumped to 10 percent. An estimated 70 percent of the bike trips were made on shared cycles. In Hangzhou, the cycling share dropped from 43 percent in 2000 to 34 percent in 2007, but then it rebounded to 37 percent by 2009 after bike sharing was introduced. In Beijing in the 1980s, more than half of all trips were made by bicycle; by 2007 this had fallen to 23 percent. Yet as more cars and trucks filled Beijing’s roads, the average car speed fell to less than 8 miles per hour in 2003, down from 28 in 1994. It is too early to gauge the impact of Beijing’s municipal bike-share program, which opened in 2012 with 2,000 cycles and plans to jump to 50,000 by 2015.

Bike-sharing cities are finding that promoting the bicycle as a transport option can lead to more mobility and safer streets for all. Bike-sharing programs are well positioned to hook people up with a bus or metro system, accommodating the last mile or so between home or work and mass transit. Having bikes ready to go on the streets encourages more people to try out biking, and once they experience its convenience, speed, and lower cost, they then advocate for further improvements to cycling infrastructure—like bike lanes, paths, and parking—making it even easier for more riders to join in. This “virtuous cycle†means that it is increasingly likely that bike sharing could soon show up in a city near you.

Stay tuned for a forthcoming release delving into more detail on bike sharing in the United States.

Recommended Comments

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.