Recent spikes in grocery bills linked to extreme weather from climate change, new research show

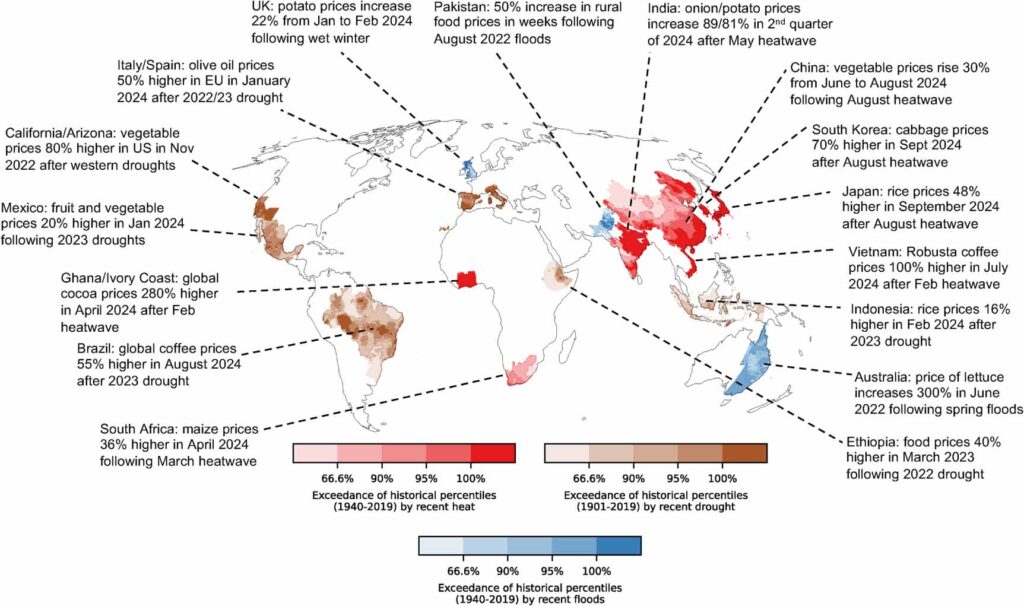

50 percent more expensive olive oil in the EU, 80 percent more expensive vegetables in the US, 300 percent more expensive lettuce in Australia. New research has calculated how price increases in 2022–2024 can be linked to climate change. And this is just the beginning.

I think we’ve all experienced how it’s been getting more and more expensive to shop groceries – with some groceries becoming unaffordable for many of us. We already know that climate change can be responsible for some of these rising grocery prices, as it causes extreme heat, drought, and heavy rainfall, which in turn lowers yields and makes the crops that are harvested more expensive. Now, a new research report by the Barcelona Supercomputing Center and the European Central Bank, among others, has traced back several unprecedented price jumps of specific goods from around the world and linked them to extreme weather events that the researchers say are fuelled by climate change.

The researchers analysed 16 different weather events that took place around the world between 2022 and 2024 and found that many of these were so unusual that each affected region hadn’t experienced anything similar prior to 2020.

The analysis identified how unprecedented drought in two major US agricultural states, California and Arizona, contributed to an 80 percent spike in the country’s vegetable prices in 2022 compared to the previous year. California, which accounts for over 40 percent of the country’s vegetable production, had its driest three-year period ever recorded, which resulted in nearly a million acres of farms fields went unplanted and $2 billion in initial crop revenue losses. And Arizona saw a dramatic drought-related water shortage that affected the Colorado River.

In 2022, the eastern parts of Australia faced record-breaking extreme flooding that resulted in a lettuce shortage and a 300 percent price increase. That same year, Spain and Southern Europe faced unprecedented droughts, which resulted in year-on-year price increases of 50 percent for olive oil across the European Union. The analysis also identified how an extreme heat wave across Asia in 2024 resulted in a 40 percent spike in vegetable prices in China and a 70 percent price hike for cabbages in South Korea, compared to the previous year.

And it was not just domestic markets that were affected by these extreme weather events, global market prices of important food commodities were also affected. In 2024, Ghana and the Ivory Coast, which produce nearly 60 percent of the world’s cocoa, experienced a prolonged drought after unprecedented monthly temperatures across the two countries. This led to a dramatic spike of around 300 percent in global market prices of cocoa compared to the previous year. The report notes that similar effects were observed for coffee following heatwaves and drought in both Vietnam and Brazil that same year.

The authors of the analysis also warn that these food price spikes comes with “knock-on societal risks”, such as rising economic inequality, an increased burden on health systems, and a destabilizing effect on monetary and political systems.

“The unprecedented nature of many of the climate conditions behind recent food price spikes highlights the ongoing threats to food security as climate change continues to push societies towards ever less familiar climate conditions. While the 2023/24 El Niño likely played a role in amplifying a number of these extremes, their increased intensity and frequency is in line with the expected and observed effects of climate change. With current policies and actions set to lead to global warming of between 2.2 °C and 3.4 °C above pre-industrial levels, unprecedented conditions are set to become increasingly common across the world.”

As the climate crisis continues unabated, extreme weather is only expected to continue. As such, the authors recommend that countries consider implementing policies that will help consumers with rising food prices – or face the risk of political and social unrest upheaval. But they also urgently stress that ultimately the only way to reduce food price inflation risks – and it consequences – is to slash greenhouse gas emissions. “This remains the fundamental lever for reducing risk,” the analysis concludes.